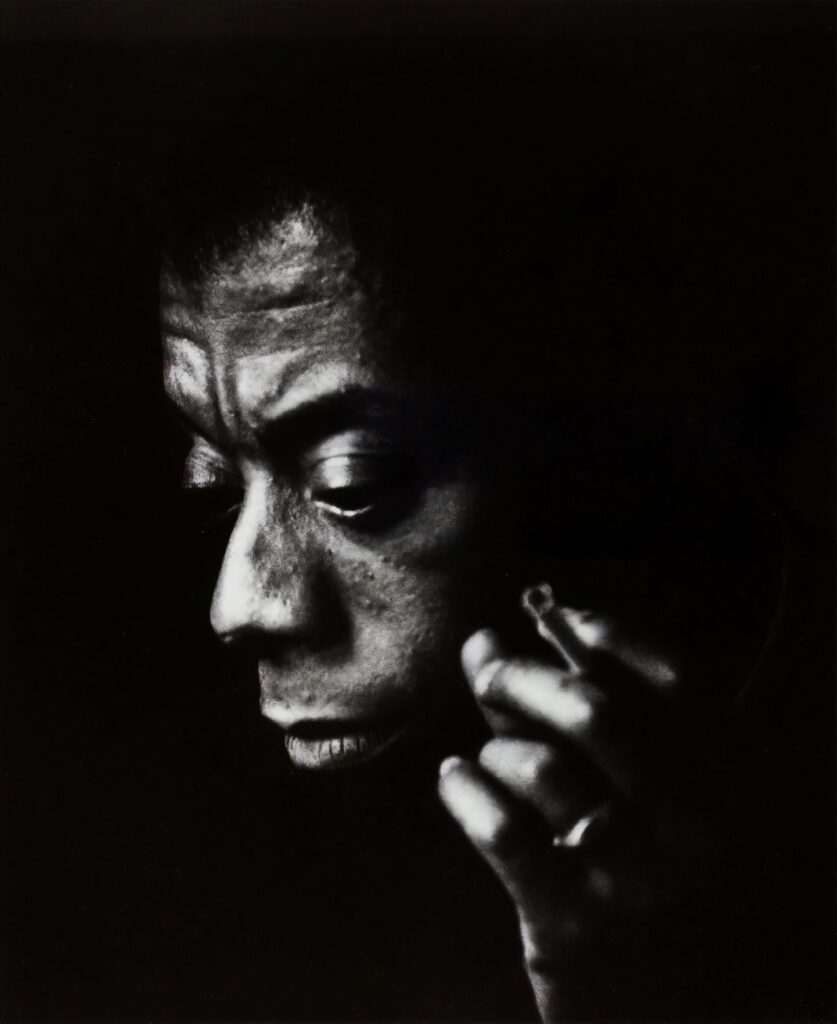

In 1948, according to the School of Life, James Baldwin “undertook that most inwardly liberating of moves. He went into exile” in France.

The idea offers a lot of appeal. There is a certain romanticism in the desperate act of exile. And there is the equally romantic notion attached to living in France. I fell by accident into this role of nomad, but it’s pleasant to believe that I backed my way into exile. Without any specific intention, the dots became connected, leading me to a reasonably financially-secure existence abroad. Not in France (although that is where I am as I write this), but in Europe. While the location may be different, the vivid sense of freedom and well-being is not.

“Crucially, Baldwin had no interest whatsoever in assimilating into French society. He wasn’t looking to swap one narrow village for another. It was exile he was after. That very particular state in which one is free not to belong anywhere in particular, to escape all tribes in order to be unobserved, anonymous, and detached.”

No matter where you go, you will be seen as a member of the tribe you came from. No disavowal is enough to convince another of the abiding loyalty you have for your own. You can escape, but you can’t disappear; you may be detached, but you are never unobserved.

Baldwin’s plunge into exile would have been driven by the scrutiny he endured as a celebrated writer residing in New York. I on the other hand have no notoriety to escape; my need for exile stems from the desire for a life as far off the grid as convenience allows, an untethered existence as below the radar as the law allows, the solitude of being a stranger in strange lands. Baldwin may have yearned to not belong anywhere in particular, but this comes at a price. Lacking any sense of belonging carries with it the empty solitude of the orphan. And no matter where you go, you will be seen as a member of the tribe you came from. No disavowal is enough to convince another of the abiding loyalty you have for your own. You can escape, but you can’t disappear; you may be detached, but you are never unobserved.

Still, exile has its advantages. There is a satisfying metaphysical sense of having embraced your own transience. Disentangled from the obligations of employment and debt, complications become nothing more than momentary aggravations to solve, not existential threats. In the extreme, you no longer have a job you could lose or a marriage that could sour. You are free to shoulder as much responsibility as you desire, to do with your time as much or as little as you choose. Being a member of any society will have its requirements and constraints, but this isn’t the essence of freedom. These bureaucratic necessities are the simple mechanics of life lived voluntarily within a developed infrastructure, the civilization we devised – the grid. Freedom is found in the daily pursuit of your own destiny, unencumbered by demands made by others, those who have no respect for your time or interest in your well-being. More than anything, freedom is the daily effort to rise above the expectation society imposes on us to conform to a way of life they likely benefits others more than yourself. Freedom offers this chance to set an individual, unencumbered course and just see what the fuck happens next.