Unless you, as an American (or English-speaker from elsewhere), move to another English-speaking country, you will face the challenge of learning a new language. You can choose not to, of course. But your experience in your new home will suffer for it. Anyone considering life abroad in a country that speaks a language different from their own should take seriously the need to speak the language. Think of yourself as a guest there. You want to be a good guest, a welcome guest. Speaking the language will improve your odds of being one.

This is not a sermon from a polyglot. In fact, the value perhaps offered here is the experience of a struggling language learner. Because the reality is that most have only varying degrees of success with acquiring a new language, while many fail. It’s worth exploring some of the reasons for this.

As adults, we underestimate just how difficult it is to learn a new language. I completed 60 hours of intensive German instruction when I worked years ago in Dusseldorf. At the end, I had an exit interview with the school founder – in English. When I expressed disappointment with my progress, he explained that no one could achieve a reasonable level of proficiency with anything less than 180 hours of training.

That was the verdict from a professional, the possibility that he wanted to sell more hours, notwithstanding. Here is my view, based on my years of attempting to learn several languages and having some success with only a few.

You have to want to – very badly.

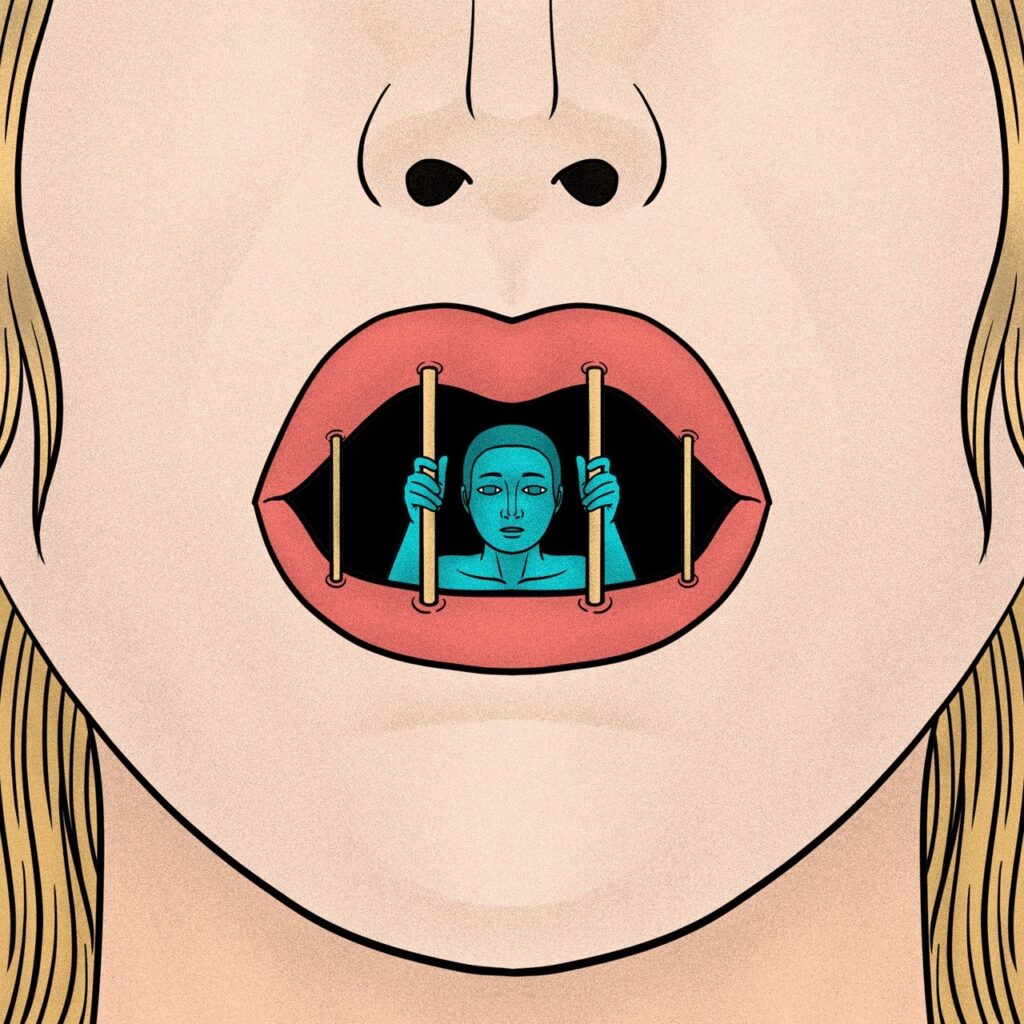

If your interest in learning the language you’ve set your sights on is lukewarm at best, you won’t learn it. Walk away. Don’t lose time or spend the money on it. Nothing can make up for lacking enthusiasm to learn the language. I tried it with a couple (Croatian and Italian). In both cases, it felt like my brain resisted the attempt. It was as if it built a protective dome inside my dome to keep out the invader. Words didn’t stick. Grammar proved to be a hopeless labyrinth. Speaking was a halting splutter that ended in a sigh.

Just be clear about your expectations. If you live in a place where the language is relatively easy – think French, Greek (yes, it’s just the alphabet that’s off-putting), Spanish – and decide Tourist Plus proficiency will get you by, fine. You should still expect to experience some isolation, but perhaps not on the scale of the Roman Ghost.

However, if you have curiosity about the people and culture of your new home; if you want to read the local news and watch any television; if you want to integrate as much as any foreigner can in that country, then you probably want it badly enough to work at it. Because you will have to work at it. Nonstop. And for the rest of your life (or as long as you choose to live there).

You must be diligent.

Once you start learning, you must never stop. There will be no days off. You must be trying to speak and understand your new language every day. The ideal situation is to be fully immersed. Imagine being surrounded only by non-English speakers, no one there to speak words that are understood in an instant. If all you hear and all you speak is the new language, you will learn it. Whether your pronunciation is accurate or your grammar is correct is beside the point. You will understand and generally make yourself understood. It will be an exhausting experience, marked by frequent embarrassment and frustration, but you will learn. It becomes only a matter of time.

Everyone learns differently. Studying grammar books and trying to memorize the rules never worked for me. I learn by listening, reading (children’s books, subtitles in the language, not English, daily news), and trying to speak. For me, the grammar follows. It begins to feel almost intuitive. You don’t fall into the habit, as adults do when faced with rigid grammar rules, of asking why. The trick in the beginning is to find what works best for you to learn as much as fast as you can. The next, harder trick is to then apply what you’ve learned without fail every day. Blabber, listen, ask if you don’t understand something, then try at the end of the day – if you’re not completely drained – to think about what you learned. Other learning habits might reinforce or accelerate the process, but the daily talk/read/listen approach is the only path to anything resembling fluency.

It helps if you’re a good listener, being a talker helps even more.

If you’re a good listener, meaning, if you listen with full concentration not only to understand but also to mimic, then this will improve your chances of success. Unless you’re saddled with a strong accent, this is the only way to good pronunciation. Concentrated listening, especially at the start of your language learning, is how you will convert an unintelligible stream of vocalization into segregated, recognizable words that hint at the overall meaning, and then into full understanding of each word and what was said as a whole.

This is especially exhausting, because the mind wanders when it doesn’t understand what’s being said. If you’re listening to a conversation without understanding much, thoughts in your mother tongue begin to intrude. You get lost in your own comfortably well-understood dialogue – unintentionally isolating yourself – and missing the opportunity to learn. Maintaining focus on what’s being said, constantly working at understanding as much as possible, is one of the hardest things to do.

If you’re one who likes to talk, it’s even better. Rapid progress comes to those who babble to anyone with little concern for making mistakes. Talkers come closest to learning like children. They talk without appearing to listen – unless to pause to ask what a certain word means – becoming proficient without the benefit of any formal instruction or self-study. They may be years into using their adopted language and still make mistakes that might draw jeers from unsympathetic locals, but they speak and understand, they integrate better, they feel more at home.

Not being self-conscious might be the biggest advantage of all.

These people – the ones who don’t care what others think – always make the fastest progress. They’re inevitably talkers, but they don’t test out a few well-rehearsed phrases, they blather. They string together sentences with an English word or two thrown in just to get out the thought, for their own learning benefit. Which is the point. These are the people who understand that no one expects them to be fluent. They believe their listeners will appreciate their effort and be accommodating, whether it’s true or not. They persevere, always with one goal in mind. Every contact with a local is a learning opportunity not to be missed. It may get messy, but it’s always better than missing that opportunity.

Those able to do this are the most likely to learn the language with a high degree of fluency. In my experience, they tend to be people who are less concerned about perfection in grammar and pronunciation and most concerned about understanding and being understood. Watching someone learn this way (sadly, I don’t) is like watching someone hack their way through jungle growth with a machete. You can see how strenuous they’re working at it, but you can also make out the progress. People with the good fortune to have this attribute, I believe, are the most likely to become polyglots.

How to tackle it.

Start by choosing the destination country and language more or less simultaneously. Choosing the language first is even better. If you’ve chosen a country but agonize about the official language, rethink. It’s better to decide on Spanish and be up in arms about whether it should be Mexico, Argentina, or Spain, rather than the other way around.

If you have some time ahead of you before you make the move, go ahead and get started. For a complete beginner, there are numerous possibilities available on-line. Keep your expectations low. This isn’t about attempting a massive download of the new language and achieving any degree of fluency. It’s about getting acclimated to it, ensuring that you’ve chosen the right language, knowing a few words and phrases when you hit the ground.

I recommend the Coffee Break series. What Mark offers without charge will meet realistic expectations. And if you’re keen, you can pay for more extensive lessons and learning aids to help you progress faster. French, Italian, and Spanish are the most comprehensive programs offered, but there are other languages to choose from.

You might want to supplement Coffee Break with something more hands-on. Babble, Duolingo, and Lingoda offer the kind of interactive learning experience that should accelerate language acquisition. Once you’re confident you will devote yourself to learning the language, adding one of these on-line programs will provide you with the feedback to confirm you’re on the right track. Depending on the time available to you and the amount of money you want to spend, you could achieve a level of proficiency that provides some confidence when you arrive in your new home.

You won’t start really learning the language until you get there. For me (and probably most people), it takes full immersion and daily contact with the language to learn it. If you force yourself to speak, and if you’re insistent about not allowing your listener to practice their English (in Europe, they always seem to speak English better than you speak their language), then you will learn.

But be realistic. It will take a few years. The rate of your progress will depend entirely on your effort. Using on-line tools can supplement this, and even accelerate it, but talking and listening to native speakers every day, watching films and television every day, and reading what you can every day, is how you will learn the language. That, and time, and perseverance, and patience.

If you decide not to tackle it.

What is life like in a country where you don’t speak the language? It will depend on the kind of person you are. But I believe for everyone there will be some sense of isolation. There will always be an undercurrent of anxiety about coping with situations that will demand some knowledge of the language. As time passes in your new home and you allow yourself to become accustomed to not speaking and not understanding, you will find yourself shrinking from contact, isolating yourself even further.

I met an elderly American man in Rome who lived there. It was only a brief exchange on a quiet street. My wife at the time and I had wandered into some vacant part of the city as we often did when we were exploring a new place and saw him seated alone on a high pavilion. He gave us both the impression of not being lost so much as misplaced, a husband waiting for a wife who will never come. He was ghost-like in his presence, somehow leaving even less of an impression on the deserted square than any mortal does. We saw him stand, then shuffle away, disappearing from sight. When we circled around, we met him. After a few words we learned he was American, had lived there for decades, and didn’t speak a word of Italian. His ephemeral appearance then made sense to us both.

Tackle it.

There is an unexpected thrill the moment you first realize you’ve understood something said to you – a proper complex sentence, I mean – without that quick mental translation into English. It’s worth experiencing. You also get a rewarding sense of accomplishment when you’re able to effortlessly string together a sentence and say it correctly without first running a grammar check.

These might seem like diminutive successes, but their sum total amounts to a lot. I get deep satisfaction from understanding someone speak another language than my own. Apart from knowing how hard it really is to acquire the ability, especially when you’re older, I can’t explain this. Except I do know that it is the one true portal to another world.

You can never know a place or a people without knowing their language.